CONSIDER YOUR PARTNERS

It’s rare that avalanches kill people with no warning. Most accidents occur when conditions indicate avalanches are likely, and the avalanches are triggered by the victim or someone in the victim's group. In many ways, avalanches aren’t the problem; people are. This is why the first step in avalanche risk management is careful consideration of your partners.

Think about your partners with regard to:

- Formal training

- Tangible qualities

- The mental shortcuts they take

You probably don’t have an unlimited choice of who to travel with, so the idea is not to be exclusive and only go with “perfect” partners. Each day, you can choose appropriate partners for your objectives, or choose appropriate objectives for your partners. Over time, these daily considerations will help you develop a great backcountry crew.

Formal Training

Avalanche training is the primary formal training to consider in your partners. In the United States, the American Avalanche Association, or A3, is the organization responsible for overseeing avalanche education. The A3 writes the guidelines that avalanche educators adhere to, so that there is consistency from one class to another. Ask your partners what level of avalanche training they have, and more importantly, watch their behaviors to see if they put their education into practice.

- Awareness/Intro level classes are very short – usually only a few hours indoors, online, or a single day outside. These classes are not intended to prepare anyone to travel in avalanche terrain. Awareness classes teach people that avalanches do occur and are dangerous, so that they can seek out further education if they do plan to travel in avalanche terrain. Intro classes teach how to identify avalanche terrain in order to avoid it.

- Rescue classes, typically one day, provide avalanche rescue practice and can be taken every few seasons to refresh. Simply being good at rescue is not an effective risk management plan, so the avalanche avoidance skills taught on the Level 1 and 2 should be prioritized over rescue skills. However, there’s also no excuse not to be good at avalanche rescue. Take a Rescue class to compliment the Level 1 and 2, practice the skills often, and take regular refresher classes.

- Level 1 classes usually take place over three days, with a significant portion of the class taking place on the snow instead of indoors or online. Because avalanche accidents require the wrong combination of people, conditions, and terrain, most Level 1 classes will focus on these three topics. A reasonable goal would be for yourself and all your partners to take a Level 1, and commit to putting the education into practice.

- The Level 2 is also typically a three-day course, and gets into more detail on the same topics as a Level 1 (people, conditions, and terrain). Often the emphasis is on conditions, to better reduce uncertainty when no regional avalanche forecast is available.

Wilderness medicine classes are very relevant to dealing with emergencies in avalanche terrain. Usually, Wilderness First Aid is introductory and lasts a few days; Wilderness First Responder is more thorough and lasts around a week; and Wilderness EMT borders on professional-level training – taking at least several weeks to achieve.

In general, all wilderness medicine classes teach students to “pack and ship” – to assess, stabilize, and evacuate patients. It’s important to recognize that far from the trailhead, there’s often not much more to be done for an injured partner. Getting them back to the trailhead without causing more harm, or deciding when to stop messing around and call for outside assistance, might be the best that you can do.

As with avalanche education, all the medical training available does no good it if can’t be implemented. Besides checking with your partners regarding their level of training, also make sure they carry first aid kits to put that training to use if it’s needed.

Tangible Qualities

Riding/skiing skill is an easy quality to observe and consider in your partners. On some days, you may not want to invite people who can’t reliably travel in the terrain you have in mind. On other days, you may appreciate the company of partners regardless of their skill.

Riding/skiing style deserves similar attention. Winter backcountry sports have become incredibly diverse, with many sub-disciplines of skiing, snowboarding, and snowmobiling that use terrain differently. Good friends in non-avalanche terrain can probably work through these differences. But in avalanche terrain, the different approaches to terrain may impact your group management and increase your risk. Either travel with people who share similar styles, or choose terrain with minimal avalanche exposure.

Navigation skills are rarely tested on easy routes under bluebird skies. Skiers and snowboarders often use established up-tracks followed by a single descent. Snowmobilers might just play ride in openings along a groomed trail. Days like these don't require a map, compass, or GPS - nor the skills to use them. But the hunt for fresh powder is likely to include storm days and less established routes. On these days, a wrong turn can lead directly to unplanned avalanche exposure, or indirectly lead to it by stressing your group's decision making.

Resourcefulness is a helpful quality when things go wrong. Equipment fails, weather changes, and plans go awry. Avalanche accident report archives are loaded with tales of people who left the trailhead with the best intentions, only to be thwarted by something that forced an error. In avalanche terrain, you want partners who have their act together to begin with, and who stay collected when thrown the inevitable curveball.

Mental Shortcuts

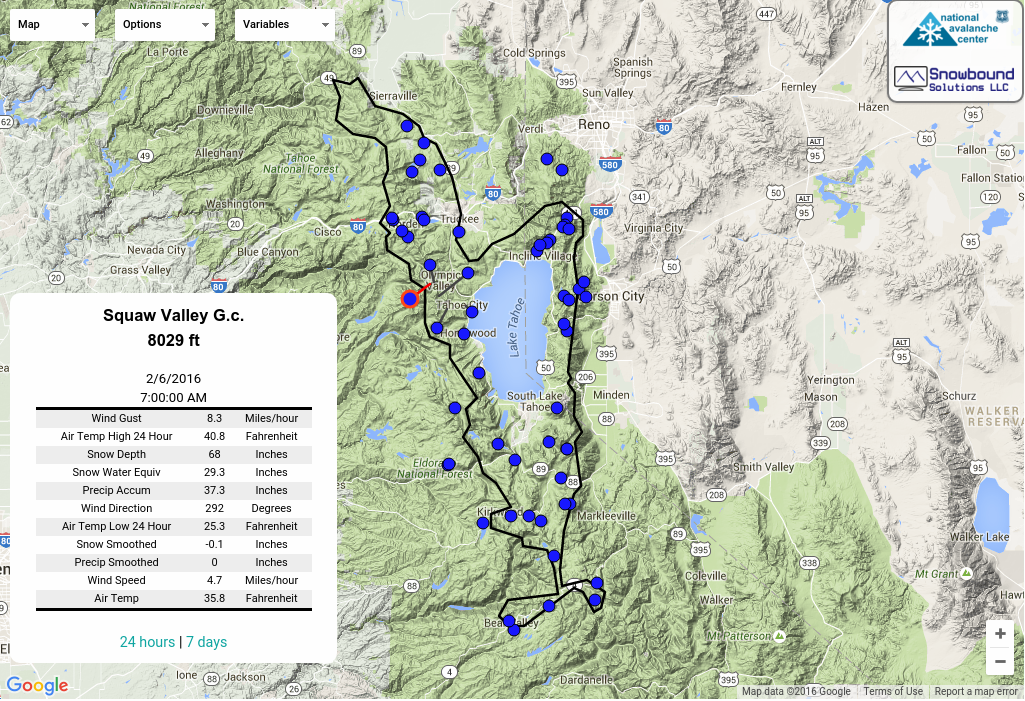

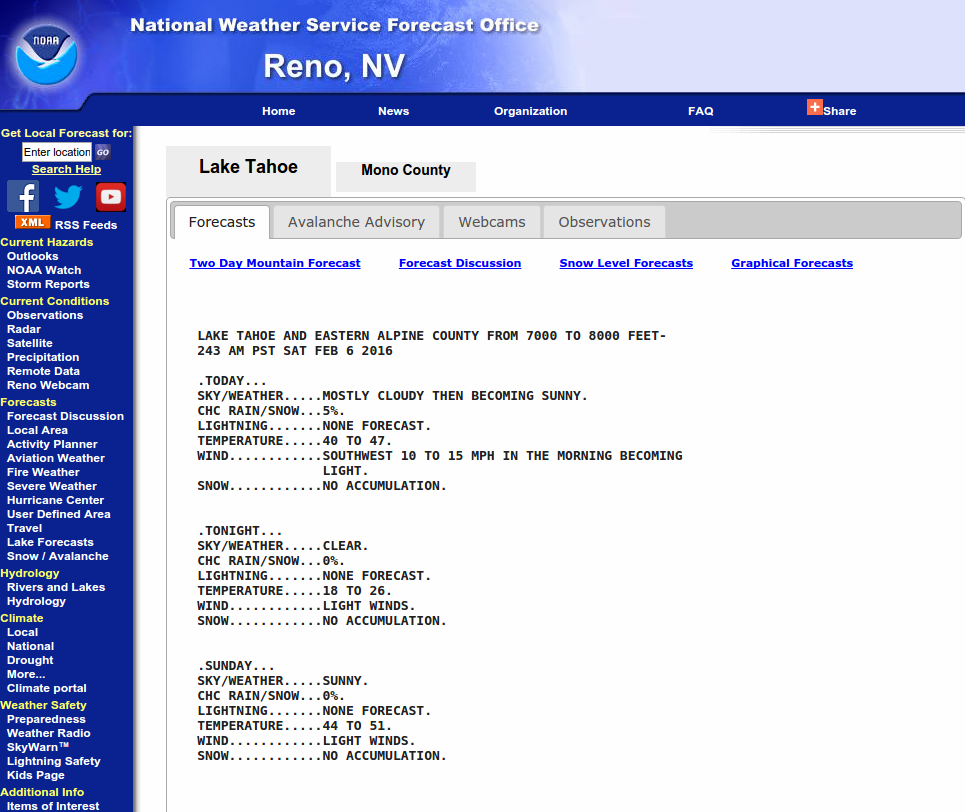

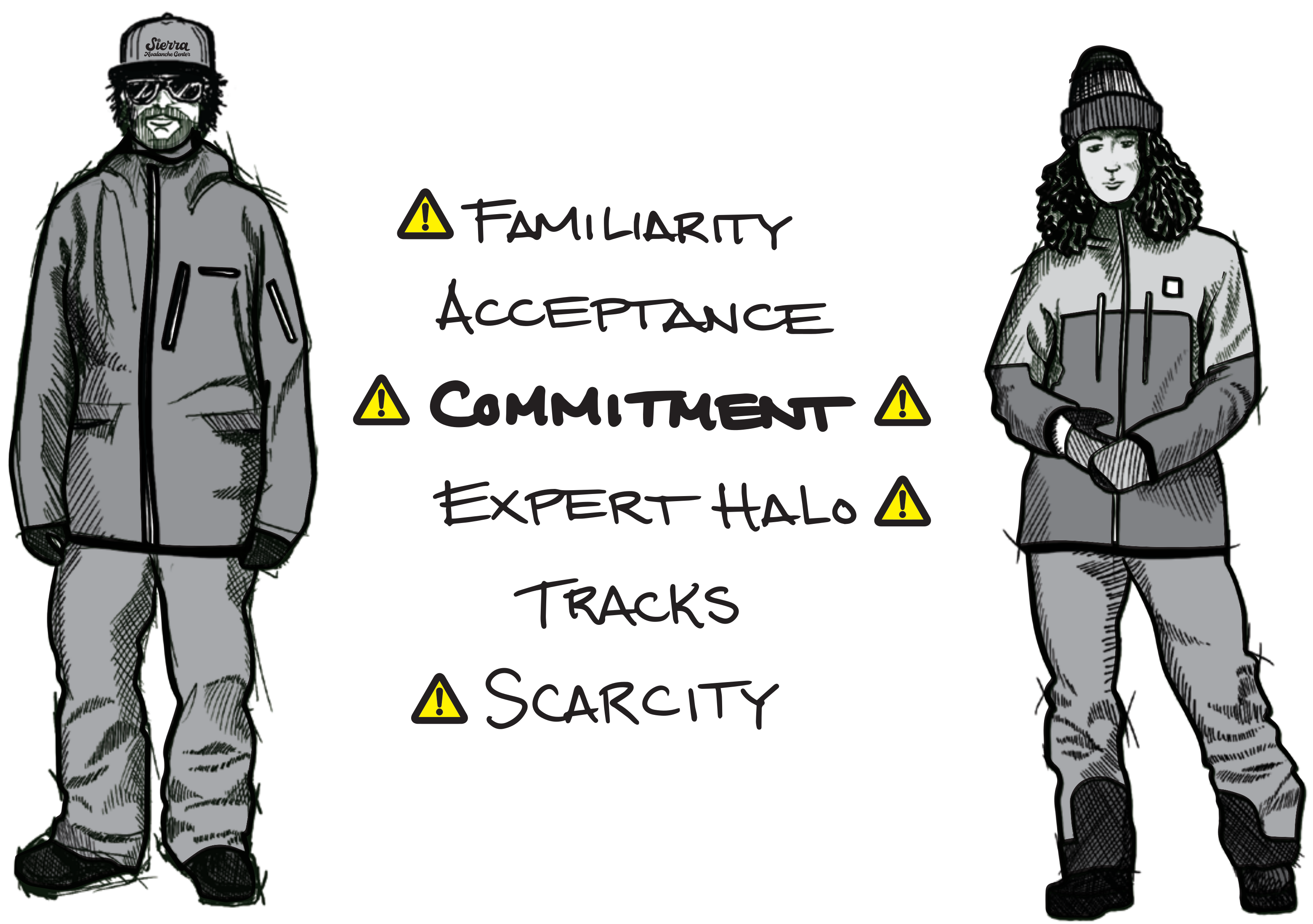

People use mental shortcuts when decision making in everyday life, and these are so common they are often subconscious. But mental shortcuts can become dangerous in avalanche terrain. Pay close attention to the shortcuts that you often take, in addition to those of your partners. If any of the following mental shortcuts are shared between group members or otherwise cause concern, account for them when you create safety margins (Adapted from “Hueristic Traps in Recreational Avalanche Accidents: Evidence and Implications” by Ian McCammon (2004)).

If any mental shortcuts are shared between group members, account for them when you create safety margins

If any mental shortcuts are shared between group members, account for them when you create safety margins

Familiarity is the tendency to feel safer in familiar settings, and to think that past experiences in these settings help predict future ones. If you haven’t seen something happen in the past, you’re less likely to spend the mental energy on it looking ahead. You may assume that familiar terrain is safe because you haven’t experienced avalanches there before, or that familiar conditions are safe because you haven’t triggered avalanches in them before.

Acceptance describes the shortcut of allowing social factors to dominate decisions. One self-explanatory version of this used to be known as “Kodak courage” and is now “doing it for the ‘gram.” But cameras or cellphones need not be involved - this shortcut can take many forms and is likely to be present anytime you recreate with other people.

Consistency/Commitment is when you’re likely to keep anchoring off an earlier decision. It’s easier than completely re-analyzing every subsequent decision, especially if you assume little has changed or if you’re too committed to acknowledge the change. Picture this happening on a well planned road trip: When you get there you’ll likely pressure yourself to continue with plans regardless of the avalanche conditions. This shortcut is used in more subtle ways and on different scales, and is most likely to be present when there are stated goals or time constraints on your day. You’re probably using this shortcut if you or your partners show less engagement when you stop to talk near your final goal, or when you're bumping up against a time constraint. If this is a pattern for you and your partners, try to plan days with several options (or open-ended goals) and minimal time constraints.

The Expert Halo is the mental shortcut that informally assigns expertise and leadership to a person on only partially relevant factors. The “natural” leader isn’t always the person with the most avalanche knowledge. It might be the most assertive person in the group, or the best skier/rider, or the common social link between partners. Make sure you don’t just follow a leader in silence, and if the expert halo is assigned to you, elicit opinions from other group members throughout the day. If you know you’re going with someone likely to assume leadership but who doesn’t actively engage in avalanche risk management, create conservative and very clear safety margins.

Tracks in the snow or other people recreating in the area may lead you to assume it’s safe just because someone else is doing it (this mental shortcut is also called Social Proof). If you’ve ever walked in a busy city, you may have used this shortcut by following a crowd across an intersection without first checking the traffic light. It can be a reasonable shortcut in that environment, but not in avalanche terrain. The first person on a slope is not always the one to trigger an avalanche, and there have been many accidents where the slope was full of previous tracks. Even if people aren’t using the same slope, their mere presence in the area might give you a false sense of security. If you travel in popular areas, your safety margins should minimize avalanche exposure. Or, create safety margins that avoid popular areas.

Scarcity is the subconscious inclination to ignore information if a scarce resource is at stake. Most of us know this as “powder fever.” Of course, fresh powder is an important goal, so when untracked snow is involved, you can probably assume that you and your partners might ignore some potentially important information. The key is to know when to plan for it. If a bad season makes untracked snow scarce, create conservative safety margins on the few powder days you have. Or if where you’re going gets tracked-out quickly, use timing margins to mitigate this mental shortcut as the day progresses.